As the winter season is at it´s best in Finland right now I felt it would be good idea to try out a pair of old skies I have stored away in the basement. This particular pair is a beautiful set. They are long and slender with a nice tapering ridge carved along the top of the ski.

|

| Image 1. Newly tared and ready to go. |

These skis are 290cm long and around a 100 years old. There are some little sign of wear on the bottom of the skies, but very little considering the age of this pair. This pair is made out of knotfree birch. These skis still have the old leather thong bindings. On some old wooden skis the leather thong binding has been substituted with the more modern "rat-trap" metal bindings but in this case the skis had been left unaltered.

|

| Image 2. Very little wear of tear on the running surface. It's hard to believe this ski is almost 100 years old. |

Finns have been skiing for a long time. The oldest ski in the world was unearthed in Salla, Northern Finland in 1938. Later carbon dating of the ski established that it was made 3298 B.C. Skis back then where wide and short and made of coniferous trees such as pine.

In historic times people used of different lengths. For 1800 years in Scandinavia, it was common to use a short ski on the left foot and a longer one on the right. Often at least in part covered in skin leg skins of wild reindeer or elk (moose), the shorter ski (or "kick ski") was used for pushing. Equally sized skis did not become common until the mid-1800s.

|

| Image 3. Archaic ski design. The Lyly (long gliding ski) and the Kahlu (short kicking ski). |

This old skiing tradition in Finland involved only one ski pole. These poles where often fitted with spearheads so that they could also be used in hunting. Elk were often chased with skis when there was a lot of snow with a strong crust. The exhausted animals where dispatched with the ski pole-spear.

Ski manufacture gradually became a small scale home industry with a specialized craftsman in every village.

|

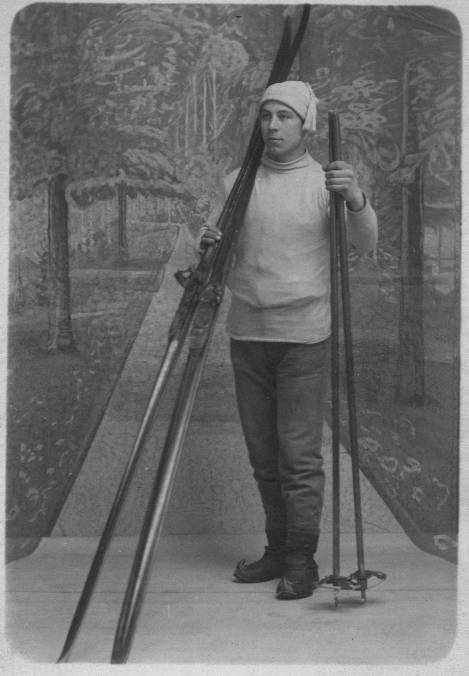

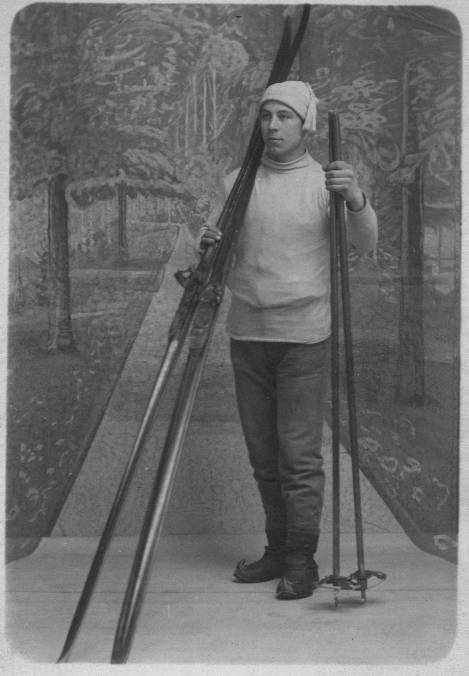

| Image 4. Skier from Pargas, Southwestern Finland 1919. |

As competitional skiing became more popular in the late 19th century it also had an impact on ski design which experienced a rapid change. Some 200 small scale factories or carpentries supplied skis to Finns in the early 20th century. Although the length of the long ski varied by region from 2.5 to over 3 meters, the long ski was always approximately 5 cm thick and 12-13 cm wide. In competitional skiing the ski tended to become shorter as the skier was using them in ski-tracks and the ski was not used for travel in deep snow. Birch was in later times the most used wood for skis in Finland. An old picture taken of a Pargas skier in 1919 gives a good look at the ski gear that was used almost 100 years ago. Notice the ski-boots with curled ends.

As I did not have a matching pair of ski-poles to go along with my skis I had to make them myself. The old poles did not have a wrist-loop at the top and they are fairly tall, almost as long as the skier. I decided to make things easy for myself so I picked up a straight grained pair of milled staves, or broom sticks at the hardware store. These should be fairly thick as they are subjected to a lot of rough handling when skiing in the forest.

I decided to go “primitive” on the ends of the poles. I had seen some ski-poles that had tips of antler and I wanted to replicate that design. I cut out two pieces of antler with simple straight joinery. These where attached to the poles using copper nails with I hammered flat in both ends (old school riveting).

The basket frame was traditionally made out of juniper and cut a few fresh branches of even thickness. Juniper is really flexible and one can bend a branch in to a nice circular shape if one is careful not to over strain the wood at knotholes.

|

| Image 5. The basket frame loops made out of juniper. |

When scraping of the bark one also has to be careful not to damage the outer surface of the frame as the wood will crack at the cut. Wood can be removed on the inner surface of the frame if the branch is of uneven thickness. The joinery of both end was simple. Just two diagonal cuts that are matched together. The joinery is attached by wrapping strong and thin cord around the splice. Small groves have to be cut on both sides of the splice so that the wrapping won´t slip of. I used sinew which I also wrapped with birch bark to cover the joint an make it water-proof.

|

| Image 6. Almost ready, the basket has to tied on the shaft and the pole tared. |

|

| Image 7. Ready for action. |

The finished ski-poles are 27mm thick and 170 cm tall. The poles used to be fairly tall, almost as tall as the skier.

Photo Credits

Image 1, 2, 5-7: Marcus Lepola

Image 3. National Board of Antiquities, http://www.nba.fi/fi/kansatieteelliset_sukset

Image 4. The Aboland photoarchive. NAU0016.